Active Managers Keep Losing as Passive Investing Grows

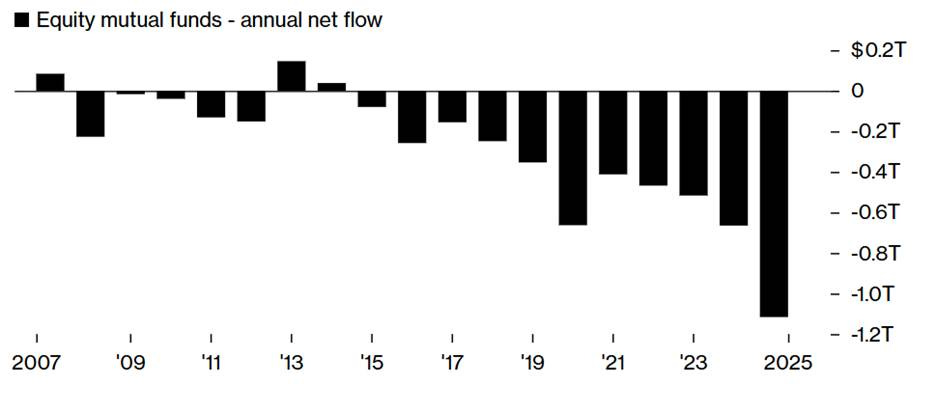

Active equity mutual funds experienced more than $1 trillion in outflows in 2025—the 11th year of net outflows and the steepest of the cycle. By contrast, passive equity exchange-traded funds attracted more than $600 billion.

For years, Wall Street has warned of an impending crisis. The narrative goes like this: as more investors abandon active management for passive index funds, price discovery will deteriorate, markets will become less efficient, and opportunities for skilled stock pickers will multiply. It’s a seductive theory that conveniently supports the active management industry’s business model.

There’s just one problem: reality refuses to cooperate.

The Warning That Never Came True

The concern about passive investing destroying market efficiency sounds logical at first. Active managers argue that index funds are “price takers” rather than “price makers”—simply buying whatever is in the index without analyzing fundamentals. As passive (systematic) strategies capture more assets, fewer investors are engaging in price discovery—researching companies and determining fair values. This should, theoretically, create pricing anomalies that active managers can exploit.

Fortunately, we have a natural experiment to test this hypothesis. In 1998, Charles Ellis’s seminal work, Winning the Loser’s Game was first published. Ellis highlighted the sobering reality that only about 20% of actively managed funds—those attempting to beat the market through security selection or market timing—were able to generate a statistically significant alpha. At the time index funds accounted for less than 10% of assets under management. Since then, we’ve witnessed unprecedented flows out of actively managed funds and into passive vehicles. If the Wall Street thesis were correct, this should have been a golden age for the remaining active managers. Instead, we’ve seen the opposite.

What the Data Actually Show

The SPIVA (S&P Indices Versus Active) scorecards tell a sobering story for active management. Despite the massive shift toward indexing, the vast majority of active funds continue to underperform their benchmarks across most time periods and asset classes. For example, the 2024 SPIVA Institutional Scorecard of U.S. Equity SMA/Wrap Managers found that 98% of multi-cap funds underperformed the S&P 1500 over the prior 10 years. Importantly, institutional funds typically have lower fees than retail funds. The underperformance isn’t marginal—it’s consistent and substantial (about 2% per annum on an equal-weighted basis).

The 2024 Scorecard also showed that, 94.1% of all domestic funds underperformed the S&P 1500 Composite Index. And of the 18 domestic fund categories (including variations of large, mid, small, value, growth, and real estate), in only two categories did fewer than 90% of the funds underperform their benchmark. The “best” category was large value funds where 87.8% of funds underperformed.

On a risk-adjusted basis, the performance was even worse, with 97.3% of domestic funds underperforming the S&P 1500 Composite Index. Fewer than one-half (48.5%) of domestic funds even survived the full 20-year period. On an equal- (asset-) weighted basis, domestic funds underperformed the 1500 Composite Index by 2.28% (1.37%).

If markets were becoming less efficient due to passive dominance, we should see active managers’ hit rates improving. We should see wider dispersions in returns as mispricing becomes more common. We should see the skilled managers pulling further ahead. None of this is happening at scale.

The Incredible Shrinking Alpha

Since Ellis’s original analysis, the landscape for active management has only grown more challenging. As detailed in my book The Incredible Shrinking Alpha. co-authored by Andrew Berkin, the proportion of actively managed funds delivering statistically significant alpha has now dropped below 2%. Several structural trends explain this persistent decline:

• Academic research has transformed alpha into beta: What was once considered manager skill is now often explained by exposure to systematic risk factors.

• The pool of less-informed investors has shrunk: As markets have become more professionalized, there are fewer easy targets.

• Competition has intensified: The rise of sophisticated institutional investors has made it harder for anyone to gain an edge.

• More dollars are chasing alpha: Increased competition for a shrinking pool of opportunities dilutes potential outperformance.

Why the Myth Persists

If the evidence so clearly contradicts the “passive investing will destroy markets” narrative, why does it persist? The answer is straightforward: the active management industry has strong incentives to promote this view. Admitting that markets can function efficiently with high levels of passive investing would undermine the justification for higher fees.

There’s also a psychological component. Many investors want to believe that skill and effort should be rewarded in investing. The idea that a simple, low-cost index fund can outperform expensive active management feels counterintuitive, even though the data consistently support it.

What This Means for Investors

The failure of the “passive investing creates opportunities” thesis has important implications. It suggests that the case for indexing, and systematic investing in general, remains strong even as it becomes more popular. Investors don’t need to worry that they’ve “missed the boat” on passive strategies or that they need to shift back to active management to capture inefficiencies.

The data suggest we’re nowhere near a tipping point where passive dominance undermines market function. If anything, the continued underperformance of active managers in an era of growing passive assets strengthens the case that most investors are better served by low-cost, diversified index funds.

The Bottom Line

Markets are remarkably adaptable systems. The shift toward passive investing represents one of the most significant changes in investment management over the past two decades, yet markets continue to function efficiently. Active managers continue to underperform, not because they lack opportunities, but because generating consistent alpha after costs remains extraordinarily difficult regardless of how many investors choose indexing.

The “anomaly” isn’t really an anomaly at all. It’s evidence that markets are more resilient and efficient than critics of passive investing assumed, and that the fundamental challenges facing active management—costs, competition, and the difficulty of sustained outperformance—persist regardless of market structure.

For investors, the lesson is clear: ignore the doomsday predictions about passive investing and focus on what the evidence actually shows. The data haven’t just failed to support the Wall Street narrative—they have actively contradicted it for decades.

Key Takeaway

The data is unequivocal: active management’s persistent failure is not a temporary phenomenon, but a structural reality. For investors, the prudent path remains clear—embrace low-cost, systematically managed funds and let the odds work in your favor.

Finally, the relentless competition among providers of passively managed funds—those constructed using transparent, evidence-based rules—has driven costs to unprecedented lows. Today, investors can access broad-market index funds with expense ratios in the single digits. Some funds, like the Fidelity ZERO Total Market Index (FZROX), charge no fees at all. This is contributing to a virtuous circle—lower costs are helping drive more investors to become passive, shrinking the pool of less informed investors who can be exploited and raising the hurdles for the generation of alpha

Larry Swedroe is the author or co-author of 18 books on investing, including his latest, Enrich Your Future: The Keys to Successful Investing

Maybe the increase in retail investors is increasing price discovery outside institutional investors

Another way to look at is if every penny was index in a single giant index fund stock prices would always move in lock step. That is obviously not happening which implies price discovery is happening. The total proportion of active management to support is probably pretty small. My guess is 5%. Another way to frame it how much selling relative to the float is required to significantly move a stock.