Private Credit Defaults

Systemic or Idiosyncratic?

The investment press sees systemic risk in every default while lenders argue idiosyncratic circumstances. Who is right? Unfortunately, financial media thrives on crisis narratives with the result is that headlines like “Private Credit in Turmoil” generates more clicks than “One BDC’s Concentrated Equity Bets Go Sideways.” This incentive structure means that the press commonly mistakes one-off defaults as something greater than they are as nuance gets sacrificed for drama. Investors need clearer, unbiased analysis.

A range of risks underlie defaults, which are catalogued below, but the presence of systemic risk is generally exaggerated and, unfortunately, never predictable. Like much else in private debt, this means diversification and loan protection are top priorities across the market cycle.

High realized losses (aka write-offs) reported by the Cliffwater Direct Lending Index (CDLI) would be the best indication that systemic risk is unfolding in the credit markets. That is not happening. Realized losses through September 2025 have been averaging an annualized 0.68% in recent years, well-below the historical 1.00% realized loss rate. Unrealized losses have effectively been zero in recent years, even when recent loan vintages are excluded from the calculation.

The recent absence of unrealized market-wide losses (write-downs) is not a sign of poor valuation procedures. Cliffwater’s research has shown that the CDLI’s unrealized losses reliably precede, but overstate, subsequent realized losses (defaults). The takeaway is that collectively, those overseeing loan valuations are doing their job.

Private debt investors get rewarded to absorb bad news, which comes from many sources. The historical default rate for the CDLI is about 2% (and recovery rate has been about 50%, resulting in credit losses of about 1%)—with roughly 10,000 middle market borrowers in the CDLI, 200 default-related news stories could be written each year. And that can create lots of panicky investors.

What’s important to understand is that most defaults reflect borrower idiosyncratic risk, unique to individual borrower circumstances. Industry risk ranks second in importance. In the last 10 years alone, energy, consumer, healthcare, and now software have temporarily elevated default levels. Manager risk ranks third, capturing the quality of underwriting on the part of lenders. Apollo, Monroe, Oaktree, Goldman, and others have endured short-term periods of above-average default losses due to poor underwriting. For a few other lenders, high default rates are persistent. Finally, there is recession risk, which is systemic across risky credits, public or private, and unforecastable. These four sources of risk can be amplified through financial risk when leverage or structuring are present. The idiosyncratic risks are why having a portfolio that is highly diversified across not only borrowers, but sectors and fund managers as well, is so important. It’s why I recommend only investing in funds that are “open architecture”, offering investors a broad, non‑proprietary lineup of underlying managers.

What about falling prices for exchange-traded BDCs? Is that a potential canary? Cliffwater’s research shows that BDC pricing, represented by the Cliffwater BDC Index, is a poor predictor of systemic risk ahead. For example, in 2011 public BDC prices dropped 30%, but subsequent CDLI values remained largely unchanged. However, BDC pricing is generally good at identifying manager and other risks, as the recently reported BlackRock write-downs demonstrated. BlackRock (formerly known as Tennenbaum) historically priced above net asset value, reflecting strong performance and a reliable investment team. After the BlackRock purchase, management changed, performance suffered, and the BDC began to consistently trade below net asset value, reaching a whopping 38% discount at year-end 2025. The public BDC market clearly foreshadowed the subsequently announced write-downs (unrealized losses).

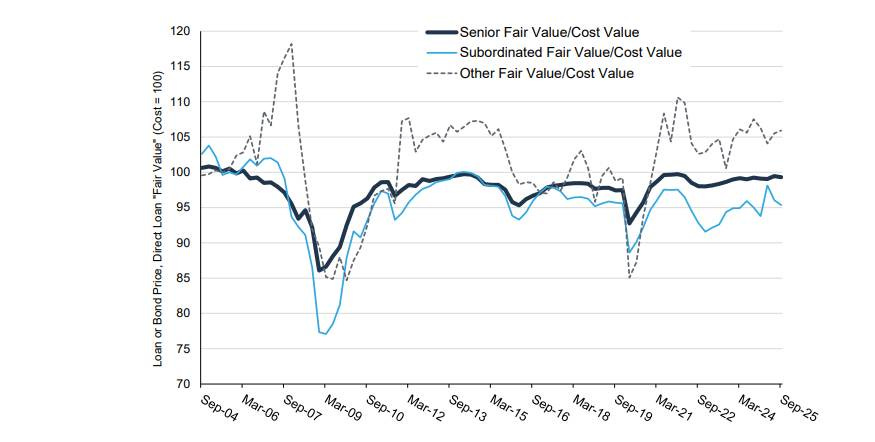

Financial risk, through subordinated debt and equity structuring, worsened BlackRock’s BDC losses. The exhibit below shows how additional volatility is introduced when relatively low-volatility senior lending is replaced by higher-volatility subordinated (second lien) and other (equity-linked) lending. Compounding structuring risk, the BlackRock BDC deployed 50% more portfolio-level leverage than the average BDC, causing perhaps manageable problems to approach unsustainable levels.

Historical Price Volatility by Loan Seniority, September 2004 to September 2025

Private debt continues to deliver investors attractive and consistent returns when enhanced diversification, loan protection, cash yield, reasonable fees, and prudent leverage levels are in place.

Larry Swedroe is the author or co-author of 18 books on investing, including his latest Enrich Your Future.