Private Capital’s Overlooked Sweet Spot, Growth Equity

Growth equity stands out as a distinct and increasingly important strategy within private equity, offering investors exposure to high-growth companies that have moved beyond the risky startup phase but are not yet candidates for traditional buyouts.

Introduction

Growth equity emerged as a formalized investment strategy in the late 20th century, pioneered by firms like Summit Partners, TA Associates, and General Atlantic. Unlike venture capital (VC), which targets early-stage startups, or buyouts, which focus on mature companies and rely heavily on leverage, growth equity invests in businesses with proven business models, meaningful revenue, and significant growth potential—typically through minority stakes and with limited use of debt. The target companies typically seek external funding to drive initiatives like new product development, operational expansion, market entry, acquisitions, or to monetize a portion of management’s ownership.

Growth equity is typically placed in a more senior position than common equity, often coming with negative control provisions and approval rights (such as annual business plans and acquisitions) to mitigate the risks of owning a minority position. Additionally, a growth equity investor will often have the right to participate in or initiate a liquidity event following a certain period of time, typically three to five years.

The strategy gained momentum after the Global Financial Crisis, as investors sought a balance between the upside potential of VC and the risk mitigation of buyouts. According to PitchBook’s “Q1 2025 Global Private Market Fundraising Report,” growth equity assets under management (AUM) topped $1.2 trillion globally in 2024, with the strategy consistently representing on average around 20% of total private equity fundraising since 2008, even amid broader market headwinds. In 2024, growth equity’s share approached one-quarter of PE funds raised (see chart below).

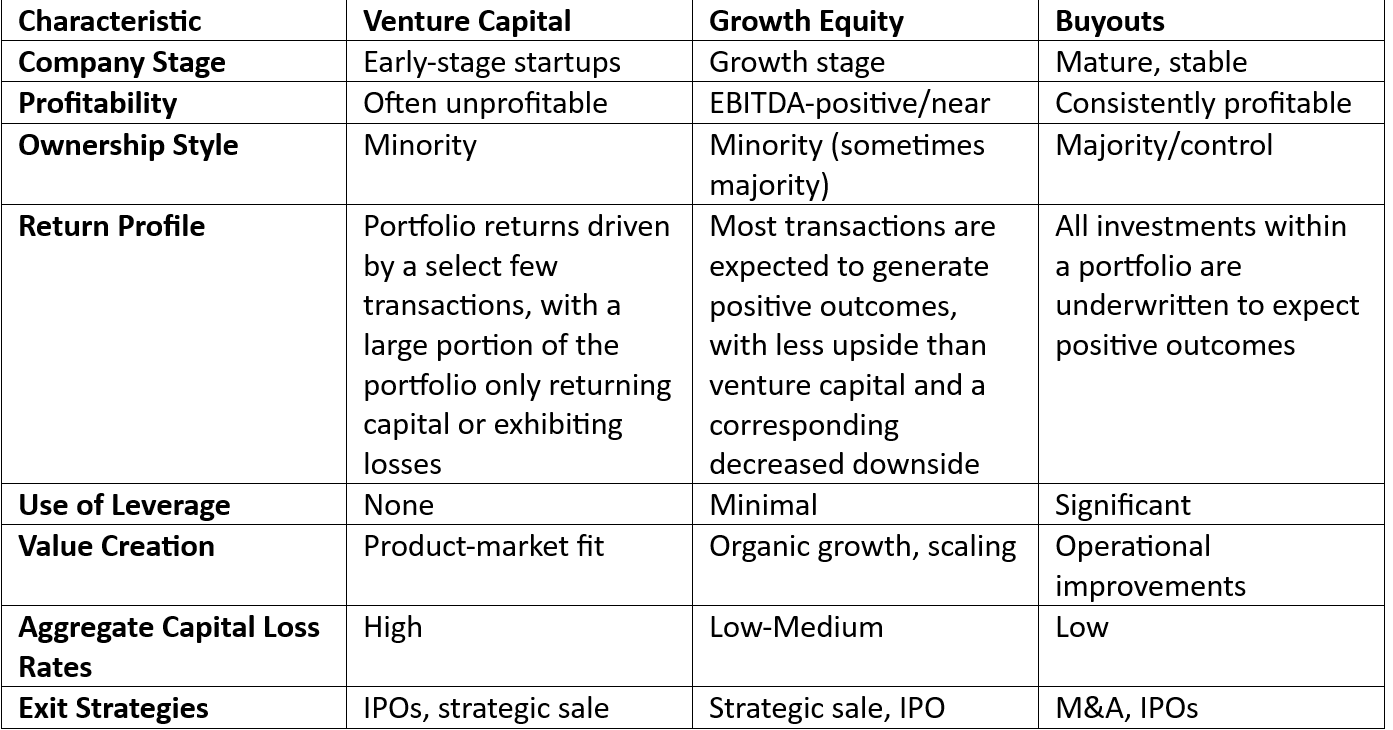

Positioning: Growth Equity vs. Buyouts and Venture Capital

Growth equity bridges the gap between VC and buyouts, targeting companies that are too mature for VC but not fully suited for leveraged buyouts. Growth equity funds generally target industries such as technology, consumer goods, and healthcare, which are known for their scalability and innovation. The companies typically exhibit:

Annual revenue growth of 15–30% or higher.

Demonstrate significant potential for expansion.

EBITDA-positive or near-breakeven status.

Established, scalable business models.

Limited or no prior institutional investment.

Founder or owner management.

Key Differentiators:

Ownership: Growth equity investors usually acquire significant minority stakes (less than 50%), maintaining management continuity and founder alignment.

Leverage: Unlike buyouts, growth equity rarely uses significant debt, relying instead on organic growth and operational expansion.

Value Creation: The focus is on fueling expansion—new products, market entry, M&A—rather than margin improvement or cost-cutting typical of buyouts.

Risk Profile: Growth equity companies have lower loss rates than early-stage VC, given their proven models and revenue traction, but offer more upside than mature buyout targets.

The Growth Equity Landscape

Growth equity is most active in technology, software, and tech-enabled services, with healthcare also gaining share. Investment sizes typically range from $10 million to $100 million, and managers vary from generalists to sector specialists. Many target founder-owned, bootstrapped companies with clean capitalization tables and strong unit economics. Growth equity managers will typically look to add value by providing capital for growth and expansion, providing strategic advice to management teams, and helping to scale operations.

Performance and Historical Returns

Growth equity has delivered robust historical returns, often outpacing both buyouts and VC over various time horizons. Its performance benefits from lower loss rates and the ability to participate in companies’ scaling phases while avoiding the binary risks of early-stage investing.

Manager selection is critical. Return dispersion among growth equity managers is high, second only to VC, with a 42%+ annual spread between top and bottom performers from 2000–2020. (Cambridge Associates Data, as of December 31, 2024.) This underscores the importance of underwriting skill and domain expertise.

Valuation Dynamics

Growth equity deals often command premium valuations, especially in high-growth sectors like software. Typical metrics include:

Revenue multiples: 3x–5x.

EBITDA multiples: mid to high teens.

Rule of 40 (revenue growth + EBITDA margin): strong if over 40%.

CAC Payback (the time it takes for a company to recoup the money spent on acquiring a new customer): strong if under 18 months.

LTV/CAC: strong if above 3x.

Investors justify these premiums by focusing on capital efficiency, sustainable growth, and clear paths to profitability.

Buyout firms are increasingly acquiring companies that have already received growth equity investments, further integrating these strategies into the broader private equity landscape.

Growth Equity Risks

Growth equity funds carry risks typical of private equity, including illiquidity and the J-curve effect, where early returns are often negative due to upfront costs and slow initial deployment of capital. These funds are also typically exposed to sector-specific risks and the lack of control over management decisions, which can lead to conflicts with company owners and leadership.

Growth equity investments require long holding periods, with exits dependent on stock market conditions and IPO environments. Prolonged holding periods may result in additional capital requirements if market conditions delay planned exits.

While there is no way to eliminate risks, investors can mitigate them in several ways. First, they can avoid the J-curve effect by investing in “evergreen” funds (interval or tender offer funds). Evergreen funds also provide diversification by vintage year reducing the impact of poor performance in a particular year or economic regime. Second, investors can diversify geographic, sector and manager risk by investing in funds that have an “open architecture” (versus investing in the fund sponsor’s proprietary deals).

As noted, manager selection is critical given the wide dispersion of outcomes. Fortunately, the academic research has found that in contrast to public markets, where there is no evidence of persistence of manager performance beyond the randomly expected, in private assets—private equity, venture capital, and private debt—the research has shown performance persistence, particularly among top and bottom quartile managers (see here, here, here, and here). The research has also found that the most reliable predictor of manager skill is the performance of funds that have already distributed most of their capital. Appraisal values and interim returns for in-flight funds, especially during market dislocations, can be misleading. Given the evidence of persistence, investors should prioritize managers with long, successful track records across multiple economic cycles, rather than relying on recent or interim performance.

These principles informed my own allocations to diversified, cost-conscious private market funds with established track records: Cliffwater’s Cascade Private Capital Fund (CPEFX), the AMG Pantheon Fund, and JPMorgan’s Private Markets Fund.

Investor Takeaways

Growth equity has matured into a distinct, compelling asset class that blends the best aspects of venture capital and buyouts while minimizing their respective risks. For investors seeking exposure to high-growth, resilient businesses with proven models and strong fundamentals, growth equity represents a “sweet spot” in private markets—offering attractive returns, lower loss rates than early-stage VC, minimal leverage, and a track record of long-term performance.

Larry Swedroe is the author or co-author of 18 books on investing, including his latest Enrich Your Future. He is also a consultant to RIAs as an educator on investment strategies.

Postscript: Thanks to Cliffwater’s Phil Huber and his paper on growth equity.