Understanding Peer Momentum

An Extension to Traditional Momentum Strategies

Momentum investing—buying recent winners and selling recent losers—has been a cornerstone strategy in equity and other (bond, commodity, and currency) markets for decades. Could the strategy be improved by looking beyond individual stock performance to capture the ripple effects that flow through economic networks? Prior research (for example, see here, here and here) has found not only that momentum industry portfolios generated significant profits, but they also explain much of individual stock momentum. Lionel Smoler-Schatz from Verdad further explored this question in his article in which he introduced the concept of “peer momentum” and demonstrated how indirect effects can enhance traditional momentum strategies.

What Did the Research Examine?

The core premise is straightforward: traditional momentum strategies look only at a firm’s own past returns to predict its future performance. This is what Smoler-Schatz called a “direct effect.” But firms don’t exist in isolation—they operate within networks of suppliers, customers, competitors, and complementary businesses. When news affects one company, it often spills over to connected firms.

His research investigated whether incorporating these indirect signals—specifically, the momentum of a firm’s peers—could improve return predictions. The hypothesis: if markets are slow to incorporate information that flows between connected companies, then peer performance should help forecast individual stock returns.

Key Findings

Industry Momentum Works

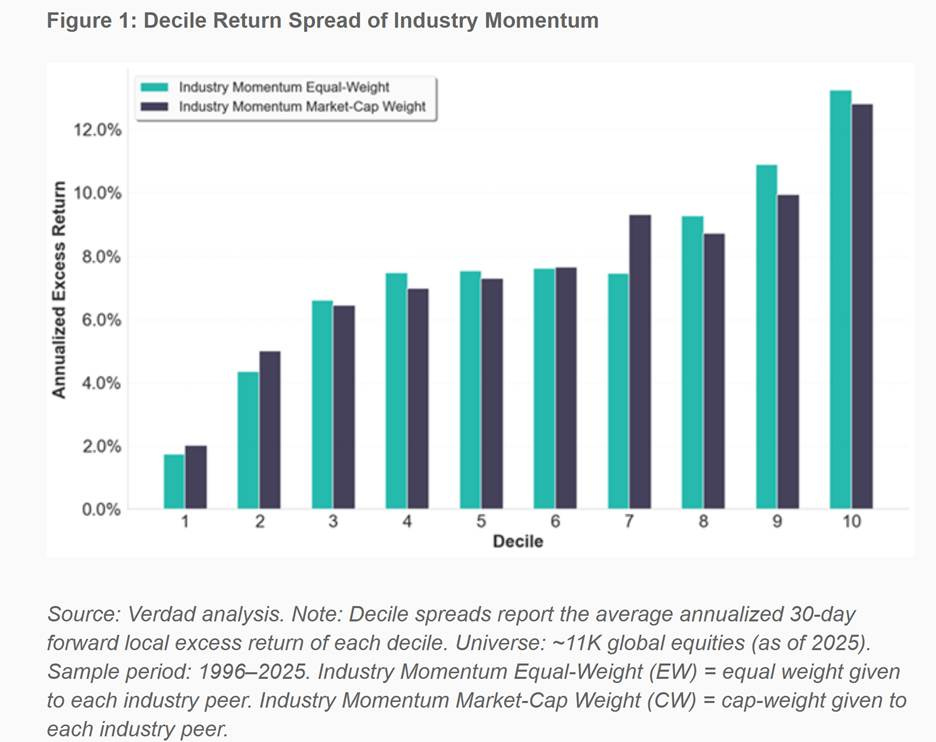

Starting with the simplest peer definition—industry membership—the research found compelling evidence. Ranking stocks by their industry peers’ momentum (rather than their own) produced annualized return spreads of 11.4% (10.8%) for equal-weighted (value-weighted) portfolios between top and bottom deciles. Importantly, this peer signal remained effective even after controlling for traditional stock-level momentum, indicating it captures genuinely different information.

Multiple Types of Connections Matter

Smoler-Schatz highlighted that industry classification is just one way to define peer relationships. Research literature documents information spillovers through various channels: customer-supplier networks (see here), technological similarities (see here), shared analyst coverage (see here), production complementarities (see here) and text-based product similarity (see here). Each of these linkages represents a pathway through which information and economic effects can propagate between firms.

Sophisticated Peer Definitions Add Value

A compelling example came from biotechnology, where traditional industry codes often fail to capture true economic relationships. Two biotech firms in the same industry classification might have completely different therapeutic focuses, while two firms in different sub-industries might both be developing similar drug modalities facing identical scientific and regulatory risks.

Verdad constructed a clinical trials database to identify biotech peers based on therapeutic focus and technological approach rather than broad sector labels. This more refined peer definition provided predictive power beyond what traditional classifications could capture—particularly valuable in a sector where standard financial metrics often fall short.

Key Investor Takeaways

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Larry’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.